Bladder Cancer Treatments

Bladder Cancer Surgery

Bladder Cancer Treatment depends on whether the bladder cancer is early and limited to the initial layers of the bladder or whether it has invaded into the deeper layer (ie. muscle) of the bladder.

The choice of bladder cancer treatments depends on a number of factors, including:

- age,

- general health; and

- extent and stage of the tumour.

Dr Kim will ascertain the most appropriate course of treatment for you.

Types of Bladder Cancer Surgery

There are a number of bladder cancer treatments available to patients diagnosed with bladder cancer include:

Cystoscopy Treatment for Bladder Cancer

Cystoscopy enables Dr Kim to directly view the inside of the urinary bladder and urethra in great detail using a “cystoscope” (the instrument used).

There are two types of cystoscope:

- Rigid cystoscope: This is a solid straight telescope, which has been in use for many years. It is used alone with a high intensity light source and a separate channel to allow other instruments to be attached

- Flexible cystoscope: This is more commonly used particularly for diagnosis and for the follow up of most bladder tumours. It is a fibre optic instrument that can bend easily and has a manoeuvrable tip that makes it easy to pass along the curves of the urethra.

This procedure may be carried out under general anaesthetic. The use of flexible instruments may allow, in many cases, the procedure to be carried out under local anaesthetic on an outpatient basis.

Cystoscopy may be indicated for the following conditions:

- Frequent urinary tract infections

- Blood in your urine (haematuria)

- Loss of bladder control (incontinence) or overactive bladder

- Unusual cells found in urine sample (abnormal cytology)

- Need for a bladder catheter

- Painful urination, chronic pelvic pain, or interstitial cystitis

- Urinary blockage such as prostate enlargement, stricture, or narrowing of the urinary tract

- Stone in the urinary tract

- Unusual growth, polyp, tumour, or cancer

Transurethral Resection of Bladder Tumour (TURBT)

If a tumour in the bladder is diagnosed on imaging or at cystoscopy, a sample of the growth is required. If it is small, only a small biopsy is required followed by cautery to stop it from bleeding.

If it is larger however it will need to be resected. This is performed by inserting a telescope through the urethra and cutting the tumour into little pieces prior to removing it from the bladder and sending it for pathological evaluation. The results will allow Dr Kim to determine the next course of treatment required.

After the TURBT, it is common to require a catheter for 1 day. After it is removed and you are sent home, there can be blood tinged urine (for up to few weeks after the procedure), and some burning sensation on urination.

Radical Cystectomy

When the bladder cancer has grown or invaded surrounding muscle or deeper layers (ie perivesical fat) radical surgical management is most likely to be necessary, usually in the form of a cystectomy which is the complete removal of the bladder.

Radical cystectomyinvolves removal of the entire bladder and in women also the uterus, fallopian tubes, ovaries, anterior vaginal wall (the front of the birth canal), and urethra. However, these reproductive organs can be spared for sexual function preservation if cancer control may not be compromised.

In men, if the prostate and bladder are both removed the procedure is known as cysto-prostatectomy.

With a radical cystectomy, removing the bladder and surrounding organs will change the way the body functions. In men, the nerves needed to get an erection are likely to be affected. Women who have their reproductive organs removed will go through menopause if they have not already.

Robotic radical cystectomy is a new advanced laparoscopic (key hole) approach that enables the surgeon to perform complex surgery through small incisions, with precision and ease. It has been shown to significantly reduce blood loss, thereby risk of transfusion, and to improve pain, and perioperative outcomes (potentially reduced hospital stay and complications).

About the Robot

Robotic surgery involves two machines, a control unit or the surgeon’s console and a patient unit. The surgeon sits at the control unit, away from the operating table, and controls the movement of the four robotic arms of the patient unit, present near the operating table.

One of the robotic arms holds and positions a 3D high definition camera through the incision in the operated area providing images of the operation site to the surgeon at the control unit. These images are:

- high resolution 3D images,

- superior to the 2D images in the laparoscopic approach.

Moreover, the images can also be magnified by 10 to 12 times. The other three robotic arms are used to hold small miniature instruments, which are used for the surgery.

These instruments are introduced through the small (8mm) incisions over the patient’s abdomen. These miniature instruments are more flexible compared to the long handled rigid instruments of the traditional laparoscopic surgery. A wide range of these instruments are available to the surgeon to perform various specialised surgical tasks.

The robotic arm cannot be programmed to do the surgery on its own. Instead, it translates the surgeon’s hand movements, at the control unit, into precise movements of the micro-instruments in the operation site, minimising tremors that may occur from unintended shaking of the surgeon’s hands. The enhanced vision and superior control of the micro-instruments helps in precise removal of the cancer while limiting damage to the nerve fibres and the blood vessels near it.

What is Urinary Diversion?

A urinary diversion is necessary when the bladder is removed to divert the flow of urine.

Types of Urinary Diversions

Once the bladder is separated from the ureters and urethra, it is necessary to provide another way to collect and drain the urine. Several options exist and depend on the overall health of the patient, the extent of cancer, and an individual’s motivation and active participation in their care.

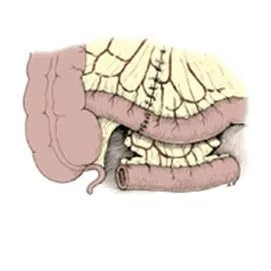

In selected patients, a portion of the intestines is used to create a new bladder or neo-bladder. The ureters are joined to one end of the neo-bladder and the other end is connected to the remaining portion of the urethra. The new bladder is constructed in such a way that it will provide a reservoir to store urine and control urine flow. You may urinate in much the same way you do now.

For patients who receive the neo-bladder, you will notice that you will not be able to hold any urine in the neo-bladder initially. This is temporary. Please buy incontinence pads or pull-ups for the first few weeks to months after the surgery. Most patients will gain control of their urine within a few months.

Neobladder: Connection of new bladder to existing urethra.

(image adapted from Campbell-Walsh Urology)

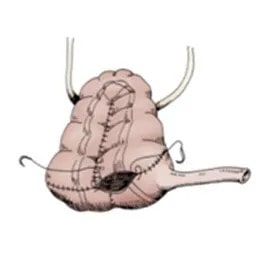

Ileal Conduit: Short segment of small intestine connecting ureters to skin.

(image adapted from Campbell-Walsh Urology)

Continent diversion: Short segment of small intestine connecting ureters to skin. (image adapted from Campbell-Walsh Urology)

Some patients are better served by creating a simpler ileal conduit. This is created using a shorter portion of intestine between the ureters to a stoma connected to the side of the abdomen. It acts as a funnel to drain urine from the kidneys to an appliance bag attached to the patient’s skin. It has the disadvantages of requiring an ostomy bag, but is a shorter and simpler operation with the least chance of post-operative or long-term complications.

Intra-Vesical Therapy

Intra-vesical treatment involves flushing the bladder with chemotherapy or immunotherapy to kill any residual tumour cells. In this procedure chemotherapy drugs are placed directly into the bladder in order to prevent the tumour recurring or to prevent it from invading the deeper layers of the bladder wall.

Intravesical chemotherapy is used only for non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer, as the chemotherapy delivered to the bladder cannot reach cancer cells in any surrounding tissues or cells that have spread to other parts of the body.

Chemotherapy for Invasive Bladder Cancer

Chemotherapy concerns the use of special cytotoxic drugs to treat cancers by either killing the cancer cells or slowing their growth. Chemotherapy drugs travel round the body and attack rapidly growing cells, which may also include healthy cells in the body as well as cancer cells. However the breaks between bouts of chemo allow the bodies normal cells to recover before the next course of chemo.

To travel the body, chemotherapy needs to enter the bloodstream and the quickest way to do this is intravenously – through a vein or artery. Other methods of administering chemotherapy may also take the form of intra-muscular injections, tablets or creams. The way you have chemotherapy depends on a number of factors including the type of cancer you have and the drugs that you are taking. Dr Kim works closely with medical oncologists who will discuss the pros and cons of chemotherapy and administer it if deemed to be beneficial.

Some cancers can be treated or cured by chemotherapy alone, while most treatments may combine chemotherapy with other procedures such as surgery or radiotherapy – this is known as multimodal therapy. Chemotherapy can be used before the main treatment to help make the tumour smaller (Neoadjuvant therapy), or after treatment to kill potential residual cancer cells that may cause problems later in treatment (Adjuvant therapy). For muscle invasive bladder cancer neoadjuvant therapy is the standard of care prior to definitive local therapy (ie. Radical cystectomy or Radiotherapy).

In some instances chemotherapy may not be able to control the cancer but may be used to relieve symptoms such as pain and help you lead as normal a life as is possible.

There are many different combinations of chemotherapy used to treat various cancers, and these may have different effects on different people.

Side Effects of Chemotherapy

While chemotherapy is useful for the killing of cancer cells in the body, as with most other treatments patients may experience side effects from the chemotherapy.

These side effects vary from treatment to treatment and from person to person but fortunately these problems may disappear with time or be managed to reduce the impact that they may cause.

The most common side effects are nausea and vomiting, fatigue (tiredness), alopecia (hair loss), muscular, nerve and blood effects as well as bowel (constipation or diarrhoea) and oral problems.

It is important that you tell the doctors and nurses if you are experiencing any side effects from your treatment so that they can discuss an appropriate course of action with you.

Radiotherapy

Radiation therapy is a cancer treatment that uses high-energy x-rays or other types of radiation to kill cancer cells or keep them from growing. There are two types of radiation therapy.

External radiation therapy uses a machine outside the body to send radiation toward the cancer. Internal radiation therapy uses a radioactive substance sealed in needles, seeds, wires, or catheters that are placed directly into or near the cancer. The way the radiation therapy is given depends on the type and stage of the cancer being treated.

If you would like to know more about bladder cancer treatment in Sydney, contact Advanced Urology now!