Bladder Cancer

What is Bladder Cancer?

Bladder Cancer occurs when abnormal cells grow and multiply quickly and uncontrollably and invade other tissues.

Bladder cancer can begin in the cells of the bladder lining. In some cases, it may spread into surrounding bladder muscle. If the cancer penetrates this muscle, it can spread to other parts of the body, usually through the bloodstream or lymphatic system.

If bladder cancer spreads to other parts of the body, such as other organs, it is known as metastatic bladder cancer.

How common is Bladder Cancer?

Bladder cancer is responsible for approximately 3% of all malignancies diagnosed in Australia each year. Bladder cancer is more common in men than women and typically affects people over 60 years of age.

What are Causes and Risk factors for Bladder Cancer?

The exact causes of bladder cancer is unknown, but is often linked to exposure to carcinogens. Often the exact cause is unknown.

Patients who are at higher risk include:

- Smokers, (4-7x more likely than non smokers)

- An older age,

- Being a male,

- Exposure to certain chemical used in the textile, petrochemical, rubber, leather, dye, paint, and print industries as well as chemicals called aromatic amines and Arsenic,

- Certain chemotherapy agents (ie Cyclophosphamide),

- Chronic bladder infections or inflammations,

- Prior Radiation,

- Schistosomiasis exposure,

- Having a family history of bladder cancer or Lynch syndrome (also called hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer or HNPCC- may have an increased risk of developing bladder or upper urinary tract cancer).

What are the Symptoms of Bladder Cancer?

Bladder cancer at an early stage of growth may not produce any noticeable signs or symptoms.

Most common symptom of bladder cancer is:

- Haematuria (bloody urine that looks red or rusty), which is usually painless and may appear only from time to time

Sometimes Irritable symptoms such as a burning sensation during urination(emptying of the bladder) and urge to urinate also indicate bladder cancer. It is not uncommon that people assume that they have infections or kidney or urinary tract stones. However, bladder cancer needs to be seriously considered especially if these symptoms persist. These symptoms are usually related to the irritation brought about by tumour growth. These symptoms are more common among patients with ‘carcinoma in situ’ (CIS), cancer that has not spread and is still “in place”. Irritable urination may be the only noticeable symptom of CIS.

As a result, it is essential to see Dr Kim to make an accurate diagnosis.

What are the Types of Bladder Cancer?

There are mainly four types of bladder cancer:

Urothelial Carcinoma(previously known as Transitional Cell Carcinoma)

Urothelial carcinoma (Transitional cell carcinoma) is the most common type of bladder cancer. It begins in the transitional cells in the inner layer of the bladder. Transitional cells are cells that change shape without becoming damaged when the tissue is stretched.

Squamous Cell Carcinoma

Squamous cell carcinoma is an uncommon type of bladder cancer in Australia. It begins when thin, flat squamous cells form in the bladder often after a long-term infection or irritation in the bladder.

Adenocarcinoma

Adenocarcinoma is also a rare cancer in Australia. It begins when glandular cells form in the bladder. Glandular cells are what make up the mucus-secreting glands in the body. These cancer cells have a lot in common with gland-forming cells of gastrointestinal cancers . Nearly all adenocarcinomas of the bladder are invasive.

Small Cell Carcinoma

This belongs to neuroendocrine tumour as cancer is derived from nerve-like cells called neuroendocrine cells. It accounts for less than 1% of bladder cancers but often grows and invades quickly. It usually needs to be treated with chemotherapy like that used for small cell carcinoma of the lung.

Bladder Cancer Grading

Bladder cancer tumours can be classified based on how the cancer cells appear when viewed through a microscope. This is known as tumour grading, and Dr Kim will describe bladder cancer as either low grade or high grade:

- Low-grade bladder tumour. This type of tumour has cells that are closer in appearance and organisation to normal cells (well-differentiated). A low-grade tumour usually grows more slowly and is less likely to invade the muscular wall of the bladder than is a high-grade tumour.

- High-grade bladder tumour. This type of tumour has cells that are abnormal-looking and that lack any resemblance to normal-appearing tissues (poorly differentiated). A high-grade tumour tends to grow more aggressively than a low-grade tumour and is more likely to spread to the muscular wall of the bladder and other tissues and organs.

What are the Stages of Bladder Cancer?

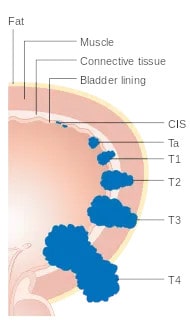

The stages of bladder cancer are indicated by Roman numerals ranging from 0 to IV.

The lowest stages indicate a cancer that’s confined to the inner layers of the bladder and that hasn’t grown to affect the muscular bladder wall.

The highest stage — stage IV — indicates cancer has spread to lymph nodes or organs in distant areas of the body.

The cancer staging system continues to evolve and is becoming more complex as doctors improve cancer diagnosis and treatment. Dr Kim uses your cancer stage to select the treatments that are right for you.

If a bladder tumour blocks a ureter (one of the two tubes that passes urine out of the kidneys and into the bladder), patients may experience pain in the side of the body between the ribs and the top of the hip. In some cases, tumour growth may constrict the urethra (the tube that passes urine from the bladder out of the body) and slow the flow of the urine stream.

Bladder cancers may also shed pieces of dead tissue, fragments of other tissue and other forms of tumour related matter that are then passed out with the urine.

If the tumour has spread beyond the bladder to surrounding tissue, the patient may experience pelvic pain. In addition, metastases from a bladder cancer may cause secondary symptoms, such as bone pain at the site of the new cancer or leg swelling (oedema) due to the involvement of the lymph nodes.

Bladder cancer that has progressed to the point of organ invasion and metastases may eventually cause the patient to lose weight and feel fatigued. Anaemia and high blood levels of urea and other metabolic by-products, often due to urinary tract obstruction, may be further indications of late-stage bladder cancer.

T (Tumour) Staging of Bladder Cancer

How is Bladder Cancer Diagnosed?

If there is blood in the urine, or any of the other symptoms mentioned are experienced, Dr Kim will need to conduct clinical assessment and arrange appropriate investigations in order to formulate an accurate diagnosis.

CT IVP (Intravenous Pyelogram)

CT scans are special x-rays that show the internal organs of your body. Dyes may also be injected allowing the doctor to see the area more clearly if there are any abnormalities in the upper urinary tract and bladder. CT IVP is the scan of choice for investigation of the upper urinary tract abnormality but requires good kidney function, and no contrast allergy.

Renal tract Ultrasound (USS)

It uses sound waves to evaluate the internal genitourinary organs. This test does not require any type of contrast medium. It is indicated when patient has any contraindication to CT IVP or risk of bladder cancer is deemed to be low (ie microscopic haematuria or no risk factors).

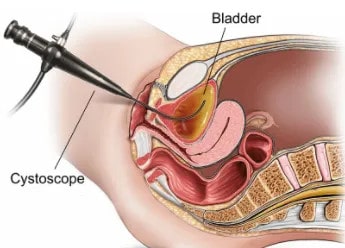

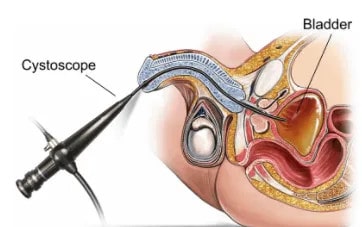

Cystoscopy

Cystoscopy enables a urologist to directly view the inside of the urinary bladder and urethra in great detail using a “cystoscope” (the instrument used). There are two types of cystoscopes.

Rigid Cystoscope

This is a solid straight telescope and is used with a high-intensity magnified light source. A separate channel allows other instruments to be attached.

It allows urologists to look at the inner lining of the bladder and check for any abnormalities or suspicious looking tissue.

Dr Kim may also take a biopsy that can be examined more closely in a laboratory allowing an accurate diagnosis to be made.

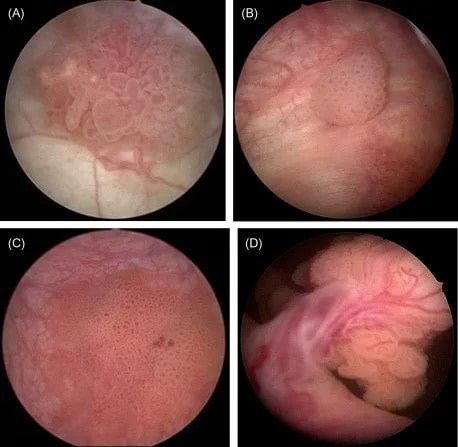

Cystoscopic appearance of Bladder cancers

Flexible Cystoscope

This is commonly used, particularly for diagnosis and for post-op follow up examinations (e.g bladder tumour removal). It is a fibre optic instrument that can bend easily and has a manoeuvrable tip that makes it easy to pass along the curves of the urethra.

This procedure may be carried out under general anaesthesia, although many patients tolerate flexible instruments well, allowing this procedure to be done under local anaesthetic on an outpatient basis.

Flexible Cystoscope in Female

Flexible Cystoscope in Male

Indications

Dr Kim may perform a cystoscopy to find the cause of many urinary conditions, including:

- Blood in your urine (haematuria)

- Unusual growth, polyp, tumour, or cancer

- Unusual cells found in a urine sample (Atypical/abnormal cytology)

- Frequent urinary tract infections

- Significant lower urinary tract symptoms not responding to behavioural modification or medications

- Loss of bladder control (incontinence) or overactive bladder (Frequent and urgent need to urinate)

- Painful urination, chronic pelvic pain, or interstitial cystitis

- Urinary blockages such as prostate enlargement, stricture, or narrowing of the urinary tract

- Stone in the urinary tract

Possible risks of a cystoscopy include:

- Discomfort

- Transient Dysuria (burning sensation on urination) or Blood in your urine (haematuria)

- Infection

People scheduled for a cystoscopy should ask Dr Kim and his staff about any special instructions

Urine Cytology

Cells found in the urine are examined under a microscope for abnormalities. This procedure is called urine cytology. This is particularly useful for high grade (aggressive) bladder or urinary tract cancers. (from the collecting system in the kidney, ureter and bladder)

What are the Treatments for Bladder Cancer?

The choice of treatments depends on a number of factors, including

- your age,

- risk of bladder cancer,

- previous treatment,

- general health and

- the extent and stage of the tumour.

There are a number of possible treatments available to patients diagnosed with bladder cancer. These include:

Non-Surgical Approaches:

A number of treatments may be used in conjunction with each other, typical examples being the use of

- Intravesical therapies such as BCG or Chemotherapy(see chemo information),

- Pre-operative (neoadjuvant) chemotherapy or immunotherapy to shrink the tumour or slow its growth in case of muscle invasive bladder cancer,

- Radiotherapy (in the setting of muscle invasive bladder cancer in combination of maximal TURBT and chemotherapy especially especially if radical cystectomy is deemed to be risky or patient preference or if symptomatic for palliation)

Surgical Approaches:

- Transurethral Resection of the Bladder Tumour (TURBT)

- Radical Cystectomy

- Urinary Diversion

Dr Kim will discuss with you to ascertain the most appropriate course of treatment for you.

Surgical Treatments for Bladder Cancer

Trans Urethral Resection of the Bladder Tumour (TURBT)

Transurethral Resection of the Bladder Tumour involves the inserting a thin tube, through the urethra and up into the bladder. The surgeon can then remove the tumour without the need for a large external incision.

Radical Cystectomy

A standard form of surgery for muscle invasive bladder cancer is a Radical Cystectomy, which involves cutting away the entire bladder and associated tissues (including prostate in men), with Pelvic Lymphadenectomy (removal of the lymph nodes within the hip cavity). Radical cystectomy in women often includes removal of the uterus, Fallopian tubes, ovaries, anterior vaginal wall (the front of the birth canal), and urethra but can be spared with the aim of preserving sexual function.

In men, it is also called a Cysto-Prostatectomy, as it involves the removal of the bladder and prostate, with Pelvic Lymphadenectomy.

Urinary Diversion

The body regulates its internal metabolites by passing blood through the kidneys, which then filter the blood and passing the wastes through the ureters into the bladder. This wasted is then discharged from the body in the form of urine.

Because some types of cancer can only be remedied by removing the bladder, another way must be found in order for the body to discharge urine. These procedures are called urinary diversion.

The most common diversion is called an Ileal Conduit – this involves taking a piece of bowel and forming a ‘pipe’ that is inserted where the bladder once was. The conduit then carries the urine from the ureters out onto the skin of the abdomen where the conduit ends in a Stoma – a small opening. Urine is then emptied into a plastic bag attached to the skin, where it can be emptied at various intervals.

Other forms of diversion involve the formation of an internal pouch made out of part of the bowel. The pouch has an inbuilt valve so that urine collects inside and does not leak through the Stoma. When it needs emptying, a small plastic tube called a Catheter can be passed through the stoma and the valve allowing urine to flow out. This is a major piece of surgery and requires much planning and recuperation time. The suitability of this procedure should be discussed with Dr Kim.

Non Surgical Treatment for Bladder Cancer

Intravesical Treatment

Intravesical treatment involves flushing the bladder with chemotherapy or immunotherapy to flush out any residual tumour cells following surgery. These drugs are placed directly into the bladder in order to prevent the tumour recurring or to prevent it from invading the deeper layers of the bladder wall.

Researchers have trialled various combinations of systemic drugs and a number of these have proven efficacy in the adjuvant treatment of bladder cancers.

Radiotherapy for Bladder Cancer

What is Radiation Therapy?

Radiotherapy uses powerful x-rays and other high-energy rays to kill cancer cells using a machine called a ‘Linear Accelerator’. Damaging the cancer cells means that they cannot grow or multiply and so they die. Normal cells are also damaged in this procedure but usually recover.

During treatment planning the radiation oncologist uses all the information gathered to develop an individual treatment plan.

Who gets Radiation Therapy?

A number of tests will be performed in order to allow doctors to determine the best course of treatment for the type of cancer for each individual. The tests include a cystoscopy and a CT scan to assess the extent of the tumour present. It is also based on patient symptoms, preference and the aim of the treatment (ie curative or palliative).

The above information will help doctors to determine whether radiation therapy is solely used or whether it can be used in conjunction with other treatments (ie chemotherapy). An accurate radiation dose to your cancer can be calculated while limiting the radiation to the surrounding areas such as the rectum.

What are the Side Effects?

The x-rays used during radiation therapy may damage normal body cells as well as cancer cells, although healthy cells usually recover from the damage. The incidence and severity of any side effects vary from patient to patient and may include

- Tiredness or fatigue

- Bladder irritation, cramps or painful urination/blood in the urine

- Diarrhoea and Bowel Cramps

- Proctitis or pain in the rectum/bleeding

- Vaginal discomfort

A variety of measures can be taken to alleviate these symptoms, discuss these issues with your doctor and radiation therapy team for the best advice for each individual.

What if Bladder Cancer is Untreated?

Untreated bladder cancer produces significant morbidity, including the following:

- Haematuria

- Dysuria (burning sensation on urination) or Irritative urinary symptoms

- Urinary retention or incontinence

- Upper urinary tract/Ureteric obstruction or kidney failure

- Pelvic or bone pain

- Constitutional symptoms (Fatigue, anorexia, weight loss)

The prognosis is poor especially if patients with muscle invasive bladder cancer are not treated. Most patients will have significant morbidity, and will die from the disease within few years of diagnosis.